Dying in chains: why do we treat sick prisoners like this?

How can you justify handcuffing a terminally ill man to his bed? An investigation into the treatment of sick prisoners

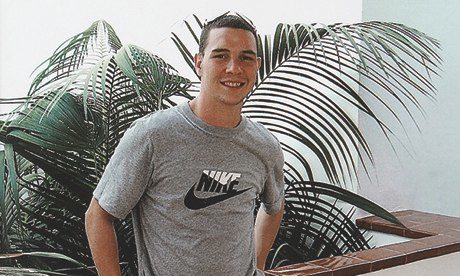

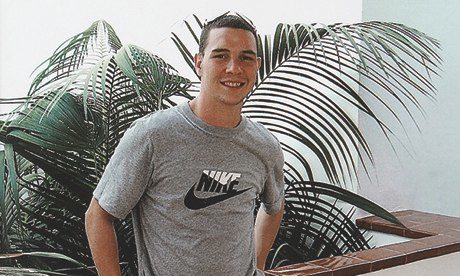

Michael Tyrrell

photographed by his daughter the day before he died: 'How much of a

security risk could a terminally ill, 65-year-old man pose? Was it

necessary to have him chained up in a way most of the British public

would not think fit for an animal?'

When Michael Tyrrell's oldest daughter Ash visited her dying

father in hospital and saw him handcuffed and chained to a prison guard,

she was so shocked that she took photographs. Tyrrell, who was almost

halfway through a 29-year sentence for drug smuggling, had throat cancer

and pneumonia. He had lost five stone in weight and barely had the

strength to move. He had not been a troublesome prisoner: after 13 years

of good behaviour, he was due to be released in 2015. The handcuffs

were taken off a few hours before he died the following day.

"How much of a security risk could a terminally ill, physically weak 65-year-old man really pose?" his daughter Maria, his middle daughter, wrote in an email to the Guardian. "Was it necessary to have him chained up in a way that most of the British public would not think fit for an animal?"

Tyrrell's three daughters believe that his death followed months of inadequate and demeaning treatment by Frankland prison, Durham. A Guardian investigation has revealed that Tyrrell's case is not an exception; that seriously ill and dying prisoners, posing no risk of escape or harm, are regularly cuffed and chained in hospital. The cases also suggest a disturbing pattern of misdiagnosis, substandard treatment and callous disregard for the families of desperately ill prisoners.

Tyrrell was an unapologetic cannabis smuggler. He lived in Antigua, a hippy pothead with a zest for life who was known as the island's first white Rastafarian. He was a cannabis evangelist, who believed it was wrong to deny anybody its healing powers. The young Tyrrell was also an aspiring Formula 3 racer; one of the world's top 70 drivers in his prime. After his sponsor was murdered, he decided to support himself with drug dealing. Always cannabis, he insisted. When the girls were young, he served a sentence in Guadeloupe for smuggling the drug. No complaints: this was his mission, those were the risks he took.

Then, in 2000, he was charged again. But this time it wasn't for cannabis: it was for attempting to import nearly half a tonne of cocaine from Bequia in the Grenadines into Britain. Tyrrell said he had been set up, and that he would only knowingly import cannabis. His daughters say they don't know whether he was telling the truth, but either way, for them, it is now irrelevant. What is relevant, they say, is the way he was left to die.

We meet in a pub close to where Ash, works, in Salisbury, Wiltshire. Ash's youngest sister, Ziffy, is over from Antigua. It is barely three months since Tyrrell died and all three daughters are still devastated. Maria, the middle one, was so distraught that she gave up a teaching job in England to return to Antigua. "I have no desire to live in a country run by people who allow this sort of thing to happen," she wrote in an email.

Ziffy's eyes are raw from crying. She says most people assume Tyrrell was a terrible father because he spent so long in prison, but that couldn't be further from the truth. He did most of the parenting when they were young, and they remember a childhood full of laughter, jokes and high-speed thrills. Ziffy was only 13 when he went to prison; she says that's when her life fell apart. She believes he was given such a severe sentence because the judge wanted to make an example of him – at the time it was suggested he had made £103m through drug money, a figure that was later downgraded to £2.3m. "Most murderers get less time than he got," she says. "He was the most anti-violent man you could imagine."

Tyrrell had first complained of severe pain after having several teeth extracted in October 2011. He was convinced his mouth had become infected, but the dentist told him there was no infection. The prison doctor then put him on antibiotics – and he remained on them for months. "I'm sorry," Ash says, "how can you do that without referring him to a specialist?"

She says he was a loving and sociable rogue, a man who would get on with all sorts. But the more pain he was in, the less sociable he became. "He was saying, 'I don't want to see anybody, my mouth hurts,'" Ziffy says. "I said, 'Why is your mouth still hurting? What's going on?' He said, 'They're ignoring me, they think I'm lying.'"

Tyrrell cancelled several appointments with the prison doctors because he had lost faith in them. "He felt if he stopped seeing those 'butchers' he might get a referral to a specialist," Ash says. "He was just being told to take more antibiotics or that there was nothing wrong with him when clearly there was."

By the time he finally got a referral, Ash says, he was malnourished and dehydrated. He had been living off melted ice-cream because anything else was too painful to swallow, but before long he couldn't even cope with that and was eating a disgusting puree he concocted himself.

The specialist found a lump on his throat in March, 17 months after Tyrrell had first complained of mouth pain. He was given a biopsy, and diagnosed with terminal throat cancer. "He was told he had a month to live without treatment, between six and 12 months if the treatment began immediately," Ash says. "The oncologist said, 'Why am I seeing you at this late stage?'"

Before Tyrrell became ill, Ziffy says, he was a big man, 18 stone, a life force. "So to walk in and look at this man, my heart broke. Honest to God, broke. I'd look at his legs, and they were half the size of mine."

Tyrrell's family claim that after his diagnosis, the treatment did not begin immediately and he received substandard support. "We asked for a blender so he could buy his own stuff from the canteen and blend it. He died without getting it." Ash says that the prison didn't allow him the pain relief he was due. "The doctors at the hospital said Dad should be getting as much pain relief as he needed, but until I complained, they limited it."

Care UK, the private company responsible for health care in Frankland, says it is "unable to release any medical details" before an inquest, but is confident the care they provided Michael Tyrrell was "timely and of a high standard".

Tyrrell went for hospital treatment five days a week. He was taken in a police van, commonly called a sweatbox. The journey took three hours each way. There was no toilet stop and Ziffy says Tyrrell was told that if he needed to urinate, he should use a plastic bottle, though as he was handcuffed, this would have been impossible.

Two months after being diagnosed with throat cancer, Tyrrell was rushed to hospital with pneumonia. When Ash got to see him, she was appalled, not only at how fast he had deteriorated but at the fact that he was handcuffed to a security guard. "It was awful. Absolutely awful. He's got the drip going into his arm, he's got an oxygen mask on, a tube into his chest, and he's handcuffed. The cuff was pushed up to keep out of the way of the drip and bandages. And when they moved it, it cut into his arm." Security guards sat in the tiny room, joking and eating hot food, as Tyrrell lay dying, handcuffed.

Four days after her father had been admitted, Ash received a phone call at 7.10am. "It was the hospital to say he'd had what they thought was a heart attack, and he wasn't in great shape. They had resuscitated him, but they wouldn't be resuscitating him again."

The handcuffs were taken off only after Tyrrell's heart attack. "He died two hours after I got there. The marks from the handcuffs were still there. There were lots of abrasions over his skin," Ash says. "There's no way anybody with a terminal illness should be handcuffed, especially when they're visibly frail." She laughs bitterly at the idea of Tyrrell running away. "He couldn't even prop himself up in that hospital bed. I was pulling him up so he could breathe."

Daniel Roque Hall with his mother, Anne: ‘I’m hardly likely to jump

out of the window or make a run for it.’ Photograph: Michael Thomas

Jones for the Guardian

Like Michael Tyrrell, 31-year-old Daniel Roque Hall smuggled drugs.

Unlike Tyrrell, he is here to tell his story – but only just. We meet at

his mother's house in Kensal Green, west London. Roque Hall, whose

father is Nicaraguan, is a bright, handsome man. When he was a child, he

was diagnosed with a terrible wasting disease, Friedreich's ataxia,

which affects co-ordination and speech; it also causes diabetes and a

heart defect that requires constant monitoring. He had a relatively

normal childhood, went to a regular school, but by the age of 15 he was

confined to a wheelchair. He went to university away from home, studying

Spanish and economics, but by then life was becoming increasingly tough

as he became more and more dependent.

Daniel Roque Hall with his mother, Anne: ‘I’m hardly likely to jump

out of the window or make a run for it.’ Photograph: Michael Thomas

Jones for the Guardian

Like Michael Tyrrell, 31-year-old Daniel Roque Hall smuggled drugs.

Unlike Tyrrell, he is here to tell his story – but only just. We meet at

his mother's house in Kensal Green, west London. Roque Hall, whose

father is Nicaraguan, is a bright, handsome man. When he was a child, he

was diagnosed with a terrible wasting disease, Friedreich's ataxia,

which affects co-ordination and speech; it also causes diabetes and a

heart defect that requires constant monitoring. He had a relatively

normal childhood, went to a regular school, but by the age of 15 he was

confined to a wheelchair. He went to university away from home, studying

Spanish and economics, but by then life was becoming increasingly tough

as he became more and more dependent.

In 2012, he was arrested for trying to smuggle £300,000 worth of cocaine in the cushion of his wheelchair from Peru through Heathrow. He says he did it only because he was in despair: his condition had started to deteriorate fast, an arranged marriage had been cancelled because his girlfriend's parents didn't want her to marry a man with such poor prospects, and his half-sister had been diagnosed with cancer. Roque Hall, who had no previous criminal record, was in pieces when he was asked to import the cocaine. The judge later accepted that he had been "groomed and manipulated".

Once he admitted guilt, it was inevitable that he would be given a custodial sentence. The only thing that could have kept him out would have been if the prison in question, Wormwood Scrubs, had said it was incapable of dealing with his complex needs. Roque Hall's mother, Anne, believes that was what the judge was expecting, and hoping, to hear; then her son would serve his sentence at home under curfew or in care.

In court it was made clear that the specialists responsible for his care believed no prison was equipped to look after him. His consultant neurologist told the court about the exercises carers need to do with him through the day and night to palliate muscle pain and constant back pain. He also has to stand in an upright wheelchair six or seven times a day, to maintain what muscle capacity he has. At home, he had at least one carer, often two, 24 hours a day. Anne says the judge looked shocked after Wormwood Scrubs insisted it was perfectly capable of looking after her son. "I jumped up and put myself in front of Daniel when the prison officers came for him, and I said, 'You're not taking him anywhere. I want the governor of Wormwood Scrubs in this court to explain exactly how they are going to look after him because it's a lie and everybody knows it's a lie.' They were all looking at me. In the end I knew I couldn't stop him being taken."

When Roque Hall was being processed at the prison, he fell from an examination couch on to his head. He told medical staff he needed to go to hospital after a fall because he was at risk of haemorrhaging, and they suggested he was faking. Instead, he was sent to a care home, where he was surrounded by patients suffering from dementia. Apart from visits to the lavatory, Roque Hall was chained to a prison guard throughout his six days in the care home.

"It was ridiculous," he says slowly, deliberately. Speech is a struggle. "I'm hardly likely to jump out of the window or make a run for it. At one time I went for a shower, so they removed the handcuffs. When I came back, they put the handcuffs on really tight. I said to the lady that they were too tight and they were pinching my skin; I asked her to loosen them and she said, no, that's how it's supposed to be."

Roque Hall went into a diabetic coma when in the care home and had to be taken to hospital. A few days later, he was judged well enough to return to Wormwood Scrubs, where it appeared that the jail was not prepared for him. Although a physio was brought in to show staff how to use his stand-up wheelchair, they refused to because they said they had not received adequate training.

He lost two stone in seven weeks and suffered dramatic muscle deterioration. While in hospital he had been diagnosed with thyrotoxicosis (caused by an overactive thyroid gland), which can cause severe weight loss. Medical staff at Wormwood Scrubs were told it was vital for his weight to be monitored regularly. "You know how often he was weighed in seven weeks?" Anne asks. "Never. And they actually had a written care plan that said he should be weighed at least once a week."

She looks at her son. "After I saw you there, I just went out and sobbed. I was beside myself." He was rushed into hospital, in chains, on 23 August. "When a nurse phoned me about 3am and said he was in intensive care, I simply said, 'Is he dying?' I think she was shocked that I'd said that. She said, well, he's very, very ill. By the time I got down there Daniel was no longer able to speak. He had a whole team of doctors and nurses around him. All he could do was make sounds like 'bleueh bleueh bleueh'. His eyes were terrified. He was emaciated, he had sores on his face, his hair was long. He'd been utterly neglected. What was he doing with sores on his face?"

It was only when his heart started to give up and he was moved to intensive care that his handcuffs were removed.

Anne, an occupational therapist, finds it traumatic to talk about even now. In the end, Roque Hall did pull through, though he spent the next six months in hospital recovering. His heart consultant said he was in metabolic breakdown, due to the thyrotoxicosis not being monitored.

When he came out of intensive care, he found himself in a ward surrounded by three prison guards. He and the guards were then moved to a room. His mother says the lack of privacy was obscene. "I was very involved in his care. I gave him his speech therapy exercises, I fed him, so the prison officers saw a lot of me. Some of them said, 'We can't give him the care he needs, he needs to be at home with his people.' But some would make notes when we talked or when the doctors came in." When Roque Hall and his mother spoke to each other in Spanish, they claim the guards forbade it.

Eventually it was accepted that Roque Hall could not be rehabilitated with the officers in the room; they were moved outside, with the door left open so they could see everything going on. Before long he was talking and making jokes, Anne says: "And I thought, this is the old Daniel."

In February, the appeal court showed "exceptional mercy" and ruled that Roque Hall should be released from prison early after his lawyers argued that the Prison Service could not meet his medical needs. "His admission to intensive care and six months in hospital would have been completely avoidable," Anne says, "if they had looked after him as healthcare staff should, and as I would have done at home, and if they had taken action much earlier, not just when he was on the verge of dying."

Roque Hall's MP, Glenda Jackson, is horrified that he was handcuffed through much of his ordeal. "It's clearly absurd that a man who could never present a physical danger to anyone should be restrained in this way," she says.

The Guardian's findings suggest that restraint is the starting point for most seriously ill prisoners, regardless of privacy and patient confidentiality issues. In May this year, John Twomey was taken from Whitemoor prison in Cambridgeshire to Peterborough hospital to undergo heart surgery. Twomey, 65, is serving 20 years and six months for masterminding a robbery at Heathrow airport. He has had three major heart attacks; after one, at Belmarsh prison, he was pronounced dead and had to be resuscitated.

Twomey went to hospital in handcuffs, with six guards escorting him. As he was wheeled into the theatre, the heart surgeon said the chain attaching him to an officer would have to be removed. It was pointed out that if his heart needed to be restarted by electric shock, the officer at the other end of the chain would also suffer a shock, possibly severe. The prison staff phoned Whitemoor, asking for permission to remove the chain. It was refused and the operation was cancelled.

On 30 May, Twomey was taken back to hospital. Following a pre-op and electrocardiogram, the surgeon said she was carrying out an angiogram, and ordered the chain to be removed. Officers remained in the theatre throughout the surgery and replaced the cuffs and chain while Twomey was still on the operating table, despite being told he would be unable to move for several hours.

In 2007, Lucy (who doesn't want us to use her last name) was taken from Peterborough prison after suffering a recurrence of a serious gynaecological problem. She was serving a sentence for a non-violent offence and had returned to jail after a day-release on licence. Despite this, she was handcuffed to a male and a female officer on the journey to her hospital appointment. Lucy says she was marched through the hospital reception "jangling like Marley's ghost", and the officers did all the talking. "I wasn't even allowed to confirm my name and date of birth; the male officer repeated my 'address' loudly enough for the whole hospital to hear," she says. She was still attached to both officers when she was called to see the doctor and had to relate her past medical history and current symptoms.

She was told she would undergo an internal examination and handed a gown. The female officer entered the changing area with her and the male officer, with chain still attached, stood outside. She says that the male officer told the doctor he would have to remain with his prisoner in the small, windowless examination room.

"I was going to have an invasive investigation, one that I wasn't overjoyed at the doctor doing, far less having a strange male observing," she says. In the end the doctor persuaded the male officer to handcuff Lucy to the couch and leave the room, leaving the female officer still attached to her. "The over-the-top security was unnecessary, offensive and inhumane," Lucy says.

The Prison Service declined to comment on any of the individual cases in this article. It told the Guardian that it restrains severely ill prisoners only after risk assessments have been carried out. "Public protection is our top priority and prison governors have a duty to mitigate the potential risks prisoners pose to the public, medical staff and other hospital users. All prisoners are risk-assessed before being escorted to hospital, to ensure security measures are proportionate and that they are being treated with dignity and respect."

But prisons and probation ombudsman Nigel Newcomen, who published a critical report on end-of-life care in custody this March, is not so sure. "The issue of inappropriate use of restraints on elderly, infirm and dying prisoners is one that needs to be addressed… While the Prison Service's first duty is to protect the public, too often the balance is not achieved between humanity and security. My office has become increasingly robust in stating where this balance hasn't been achieved."

Kyal Gaffney died, aged 22, three weeks after being sent to prison

for careless driving under the influence. Photograph: collect picture by

Murdo MacLeod for the Guardian

Mary Currie has left her old home and moved several times in

a desperate attempt to escape her past. Her son, Kyal Gaffney, died in

prison in November 2011, three weeks after being convicted of careless

driving under the influence. Mary and her daughter Justine have been

left trying to put their lives back together, but it isn't proving easy.

Kyal Gaffney died, aged 22, three weeks after being sent to prison

for careless driving under the influence. Photograph: collect picture by

Murdo MacLeod for the Guardian

Mary Currie has left her old home and moved several times in

a desperate attempt to escape her past. Her son, Kyal Gaffney, died in

prison in November 2011, three weeks after being convicted of careless

driving under the influence. Mary and her daughter Justine have been

left trying to put their lives back together, but it isn't proving easy.

They sit in a living room, surrounded by religious plaques and figurines promising hope and peace, talking about the son and brother who had been an A* pupil at GCSE, with ambitions to be a bilingual lawyer. Then, at 17, his best friend was killed in a car crash. That was when things started to go wrong. Gaffney withdrew from his many friends, became addicted to cannabis, stopped working at school. His A-level results were disappointing and he decided not to go to university. Although he was depressed, he didn't give up entirely. He became a porter, then a healthcare assistant in the hospital Mary worked in as a manager, wrote songs and befriended a boy called Devland Barnes-Bromfield. They soon became inseparable.

It was 2 July 2010, Barnes-Bromfield's 19th birthday, and Gaffney had been telling Mary all day how they were going to celebrate: they were going to get a taxi to a local club and make a night of it. But late in the evening there was a change of plans and he announced he was going to drive to Leamington, 20 miles away, to pick his mate up from another club.

The boys didn't stay long: Barnes-Bromfield and his friends had been involved in a minor fracas. Gaffney, one of life's peacemakers, according to his mother, tried to sort it out, had a bottle of cider, chatted up a girl, then the two boys headed off. On the way home, Gaffney hit a tree: Barnes-Bromfield died instantly. Gaffney was left in a coma, and it was a miracle he survived. He severed the main artery in his leg. "He lost enough blood to have killed him," Mary says. "I remember kissing his head, his face held between two blocks, completely splattered in dry blood. His leg wasn't recognisable as a leg."

After an eight-hour operation, he was kept in a medically induced coma for 10 days; he had 11 operations within two weeks of the accident. Gaffney couldn't remember anything of the crash (let alone the fact that Barnes-Bromfield had been lying dead on top of him when he was rescued, which might well have saved his life). When he was told his friend had died, he refused to believe it. "It was like I hit him on the head with two bricks," Mary says. "Then he just let out the most awful noise. It came from right in here." She points to her heart. "It was like a cat being murdered. He was screaming that it should have been him and he didn't want to live. Then he started pulling out the wires."

Gaffney was initially suicidal, but gradually became positive. He decided he had to make something of his life for his friend's sake. But Barnes-Bromfield's family blamed Gaffney for his death, and wanted to see him prosecuted. Gaffney was charged with careless driving under the influence of alcohol. He was in fact only 0.1ml over the limit after his one bottle of cider. His lawyers told him that if he pleaded guilty, he would be unlikely to face a custodial sentence.

Gaffney was unwilling to accept that he was over the alcohol limit, but he did tell his mother that he had smoked cannabis that evening. Mary knew then that her son would go to jail. Medical experts argued that he should be allowed to serve his sentence on tag at home. "His doctors said they didn't think he should go to prison because he had everything in place in the community for his medical care. His counsellor actually wanted to put him into the psychiatric unit to protect him from going to prison." Gaffney was sentenced to 21 months.

Mary and Justine are convinced the prison, HMP Hewell in Worcestershire, made everything as tough as possible for him. Mary says that the first time she visited him, he had on only one shoe because the prison had not given him his surgical footwear. He was struggling to walk on his crutches and was told he had to climb three flights of stairs to get his pain relief. "And the prison officer is there saying, come on, you can do it faster than that. We found out afterwards, to add insult to injury, that there's a lift in his block." On her first visit, Gaffney complained to his mother of cold, and said he was bunged up. By her second visit, she was worried about his condition. Like Michael Tyrrell, he was prescribed pain relief, to be topped up when necessary – but she says he was denied the top-up and was in agony.

Part of the problem was that Gaffney would not admit just how severely disabled he was. "He told me not to make a fuss," Mary says. "He didn't want to appear to be a wuss. I'd phoned in the week, asked to speak to healthcare, and they wouldn't let me because Kyal was over 18, so they just put me through to the chaplaincy. He looked really poorly on the second visit, and I was concerned because his nose had been bleeding and he'd been bringing up blood for five days. "

Mary and Justine made one final visit to Kyal, on 4 November 2011. "I was absolutely appalled," Mary says. She does slow breathing exercises – three inhalations followed by heavy exhalations – to control her emotion.

"I couldn't believe my eyes," Justine says. "He just looked completely white, and all you could see was this massive bruise on his forehead. We didn't even say, 'Hello, how are you?', just, 'Oh my God, you've been beaten up." But he hadn't been.

"As he started talking, we could see his tongue looking as if it had blood blisters on it," Justine says. "We thought he'd been hit from the back, had hit his head and bitten his tongue. He said, 'No, I had a nosebleed last night and I woke up with all these things on my tongue.' He rolled up his sleeve and he had a massive bruise on his arm. He was really disoriented and his eyes looked glazed. To start with I thought he'd been smoking weed again. I cried all the way home after the visit. I just had this feeling I wasn't going to see him again."

"I phoned the prison when we got home," Mary says. "By this time the chaplaincy had gone and I said, with the greatest respect, it's not a spiritual matter, it's a medical matter. And they said, well, the chaplaincy deals with it and they're not here now, so you'll have to get in touch with them tomorrow."

Kyal Gaffney's mother Mary and sister Justine were with him when he

died – as were his guards. Photograph: Murdo MacLeod for the Guardian

Four days later, Gaffney was diagnosed with leukaemia and rushed into

hospital. Again there were vital delays: his blood was taken in the

morning but not tested till the evening. He was in an observation room

from 9.45pm to 2am, bleeding from his nose. He had suffered a cerebral

haemorrhage. All this time he was handcuffed to a prison guard.

Kyal Gaffney's mother Mary and sister Justine were with him when he

died – as were his guards. Photograph: Murdo MacLeod for the Guardian

Four days later, Gaffney was diagnosed with leukaemia and rushed into

hospital. Again there were vital delays: his blood was taken in the

morning but not tested till the evening. He was in an observation room

from 9.45pm to 2am, bleeding from his nose. He had suffered a cerebral

haemorrhage. All this time he was handcuffed to a prison guard.

At 2.15am he became unconscious. "He was in the last hours of his life and they just put him in an observation room with a brown sick bowl, and left him to die," Mary says through a cascade of tears. He was clinically brain dead, still handcuffed to a prison guard. It was only when doctors insisted that the chains be taken off for a CT scan, that they were removed.

"They phoned me up at 3.45am and told me that Kyal had been taken to hospital," Mary says. "I said, oh, we're due to visit him later, will we be able to see him in hospital?" She breathes in deeply. "I asked what was wrong and the man from the prison said, 'You need to go to the hospital, his pupils have blown.'" They really expressed it like that? "Yes. If I wasn't a medical-type person, I wouldn't have known what it meant. But I did know: it means you've bled in your brain." She swallows and breathes. "When we got there, we were taken into a little office and this doctor came and asked us all to sit down."

Two years on, Mary still finds it hard to believe, let alone talk about, what she witnessed. The doctors thought there was one last chance to save her son, by rushing him for emergency surgery at a more specialised hospital. "They needed a doctor and two nurses in the ambulance, but the guards insisted they had to go with him, and there wasn't room."

"I said, 'You should be ashamed of yourselves,'" Justine says. "My brother needs to get in that ambulance, and you are having an argument with medical staff because you want to get in there. He's in a coma and you still think you need to stop him escaping?" In the end, the medical staff agreed to travel with just one nurse and the two guards, but by then it was too late. It was now 6am, four hours since Gaffney had gone into a coma, and doctors decided nothing could be done.

Indignity was heaped upon indignity. Around 30 friends arrived to say goodbye to him before the life-support machine was turned off. "The guards didn't leave the room till after we arrived," Justine says. "They wouldn't allow any of his friends to go in because technically he was still a prisoner. The guards were still there even when the machine was turned off. We said, 'We don't need you here now, you know he's dead. Is that not enough for you?'"

Kyal Gaffney died, aged 22, on November 9 2011. The inquest into his death heard a catalogue of misdiagnoses and unnoticed symptoms, and an occasion when the prison doctor refused to see him. A narrative verdict concluded: "There were a number of missed opportunities for further intervention prior to 7 November 2011. The jury concludes that had further intervention occurred, then it is more likely than not that an intracerebral haemorrhage could have been avoided." In April, a report into HMP Hewell by HM Inspectorate of Prisons concluded that the jail "provided an unsafe and degrading environment".

Ask most prisoners what their main fear is and they will tell you it is getting ill in jail – a fear that seems to have been exacerbated by the privatisation of healthcare services in prison and the impending withdrawal of legal aid for prisoners to challenge neglect by prison staff. While the cases examined here are extreme, the charity Inquest believes they are indicative of common failings in prison healthcare. Deborah Coles, co-director of Inquest, says: "This demonstrates a shocking abuse of power, and a total lack of humanity towards dying, seriously ill and disabled prisoners. These are not isolated cases but illustrative of a systemic pattern where principles of humanity and decency have been usurped in the interests of security, and where the use of restraints is the default rather than the exception. Such policy interpretation must be urgently reviewed to prevent further ill-treatment and to ensure restraint is used only in the most exceptional circumstances."

Back in Salisbury, Michael Tyrrell's daughters are convinced that if he had been diagnosed earlier, he would still be alive. They point to a photograph of a cheerful, larger-than-life man happily listening to the Salvation Army in prison, taken just a few months before he died. But for now this is not the way they remember him. The image they are left with is of an emaciated man lying in a hospital bed, chained to a prison guard, waiting to die.

"How much of a security risk could a terminally ill, physically weak 65-year-old man really pose?" his daughter Maria, his middle daughter, wrote in an email to the Guardian. "Was it necessary to have him chained up in a way that most of the British public would not think fit for an animal?"

Tyrrell's three daughters believe that his death followed months of inadequate and demeaning treatment by Frankland prison, Durham. A Guardian investigation has revealed that Tyrrell's case is not an exception; that seriously ill and dying prisoners, posing no risk of escape or harm, are regularly cuffed and chained in hospital. The cases also suggest a disturbing pattern of misdiagnosis, substandard treatment and callous disregard for the families of desperately ill prisoners.

Tyrrell was an unapologetic cannabis smuggler. He lived in Antigua, a hippy pothead with a zest for life who was known as the island's first white Rastafarian. He was a cannabis evangelist, who believed it was wrong to deny anybody its healing powers. The young Tyrrell was also an aspiring Formula 3 racer; one of the world's top 70 drivers in his prime. After his sponsor was murdered, he decided to support himself with drug dealing. Always cannabis, he insisted. When the girls were young, he served a sentence in Guadeloupe for smuggling the drug. No complaints: this was his mission, those were the risks he took.

Then, in 2000, he was charged again. But this time it wasn't for cannabis: it was for attempting to import nearly half a tonne of cocaine from Bequia in the Grenadines into Britain. Tyrrell said he had been set up, and that he would only knowingly import cannabis. His daughters say they don't know whether he was telling the truth, but either way, for them, it is now irrelevant. What is relevant, they say, is the way he was left to die.

We meet in a pub close to where Ash, works, in Salisbury, Wiltshire. Ash's youngest sister, Ziffy, is over from Antigua. It is barely three months since Tyrrell died and all three daughters are still devastated. Maria, the middle one, was so distraught that she gave up a teaching job in England to return to Antigua. "I have no desire to live in a country run by people who allow this sort of thing to happen," she wrote in an email.

Ziffy's eyes are raw from crying. She says most people assume Tyrrell was a terrible father because he spent so long in prison, but that couldn't be further from the truth. He did most of the parenting when they were young, and they remember a childhood full of laughter, jokes and high-speed thrills. Ziffy was only 13 when he went to prison; she says that's when her life fell apart. She believes he was given such a severe sentence because the judge wanted to make an example of him – at the time it was suggested he had made £103m through drug money, a figure that was later downgraded to £2.3m. "Most murderers get less time than he got," she says. "He was the most anti-violent man you could imagine."

Tyrrell had first complained of severe pain after having several teeth extracted in October 2011. He was convinced his mouth had become infected, but the dentist told him there was no infection. The prison doctor then put him on antibiotics – and he remained on them for months. "I'm sorry," Ash says, "how can you do that without referring him to a specialist?"

She says he was a loving and sociable rogue, a man who would get on with all sorts. But the more pain he was in, the less sociable he became. "He was saying, 'I don't want to see anybody, my mouth hurts,'" Ziffy says. "I said, 'Why is your mouth still hurting? What's going on?' He said, 'They're ignoring me, they think I'm lying.'"

Tyrrell cancelled several appointments with the prison doctors because he had lost faith in them. "He felt if he stopped seeing those 'butchers' he might get a referral to a specialist," Ash says. "He was just being told to take more antibiotics or that there was nothing wrong with him when clearly there was."

By the time he finally got a referral, Ash says, he was malnourished and dehydrated. He had been living off melted ice-cream because anything else was too painful to swallow, but before long he couldn't even cope with that and was eating a disgusting puree he concocted himself.

The specialist found a lump on his throat in March, 17 months after Tyrrell had first complained of mouth pain. He was given a biopsy, and diagnosed with terminal throat cancer. "He was told he had a month to live without treatment, between six and 12 months if the treatment began immediately," Ash says. "The oncologist said, 'Why am I seeing you at this late stage?'"

Before Tyrrell became ill, Ziffy says, he was a big man, 18 stone, a life force. "So to walk in and look at this man, my heart broke. Honest to God, broke. I'd look at his legs, and they were half the size of mine."

Tyrrell's family claim that after his diagnosis, the treatment did not begin immediately and he received substandard support. "We asked for a blender so he could buy his own stuff from the canteen and blend it. He died without getting it." Ash says that the prison didn't allow him the pain relief he was due. "The doctors at the hospital said Dad should be getting as much pain relief as he needed, but until I complained, they limited it."

Care UK, the private company responsible for health care in Frankland, says it is "unable to release any medical details" before an inquest, but is confident the care they provided Michael Tyrrell was "timely and of a high standard".

Tyrrell went for hospital treatment five days a week. He was taken in a police van, commonly called a sweatbox. The journey took three hours each way. There was no toilet stop and Ziffy says Tyrrell was told that if he needed to urinate, he should use a plastic bottle, though as he was handcuffed, this would have been impossible.

Two months after being diagnosed with throat cancer, Tyrrell was rushed to hospital with pneumonia. When Ash got to see him, she was appalled, not only at how fast he had deteriorated but at the fact that he was handcuffed to a security guard. "It was awful. Absolutely awful. He's got the drip going into his arm, he's got an oxygen mask on, a tube into his chest, and he's handcuffed. The cuff was pushed up to keep out of the way of the drip and bandages. And when they moved it, it cut into his arm." Security guards sat in the tiny room, joking and eating hot food, as Tyrrell lay dying, handcuffed.

Four days after her father had been admitted, Ash received a phone call at 7.10am. "It was the hospital to say he'd had what they thought was a heart attack, and he wasn't in great shape. They had resuscitated him, but they wouldn't be resuscitating him again."

The handcuffs were taken off only after Tyrrell's heart attack. "He died two hours after I got there. The marks from the handcuffs were still there. There were lots of abrasions over his skin," Ash says. "There's no way anybody with a terminal illness should be handcuffed, especially when they're visibly frail." She laughs bitterly at the idea of Tyrrell running away. "He couldn't even prop himself up in that hospital bed. I was pulling him up so he could breathe."

Daniel Roque Hall with his mother, Anne: ‘I’m hardly likely to jump

out of the window or make a run for it.’ Photograph: Michael Thomas

Jones for the Guardian

Like Michael Tyrrell, 31-year-old Daniel Roque Hall smuggled drugs.

Unlike Tyrrell, he is here to tell his story – but only just. We meet at

his mother's house in Kensal Green, west London. Roque Hall, whose

father is Nicaraguan, is a bright, handsome man. When he was a child, he

was diagnosed with a terrible wasting disease, Friedreich's ataxia,

which affects co-ordination and speech; it also causes diabetes and a

heart defect that requires constant monitoring. He had a relatively

normal childhood, went to a regular school, but by the age of 15 he was

confined to a wheelchair. He went to university away from home, studying

Spanish and economics, but by then life was becoming increasingly tough

as he became more and more dependent.

Daniel Roque Hall with his mother, Anne: ‘I’m hardly likely to jump

out of the window or make a run for it.’ Photograph: Michael Thomas

Jones for the Guardian

Like Michael Tyrrell, 31-year-old Daniel Roque Hall smuggled drugs.

Unlike Tyrrell, he is here to tell his story – but only just. We meet at

his mother's house in Kensal Green, west London. Roque Hall, whose

father is Nicaraguan, is a bright, handsome man. When he was a child, he

was diagnosed with a terrible wasting disease, Friedreich's ataxia,

which affects co-ordination and speech; it also causes diabetes and a

heart defect that requires constant monitoring. He had a relatively

normal childhood, went to a regular school, but by the age of 15 he was

confined to a wheelchair. He went to university away from home, studying

Spanish and economics, but by then life was becoming increasingly tough

as he became more and more dependent.In 2012, he was arrested for trying to smuggle £300,000 worth of cocaine in the cushion of his wheelchair from Peru through Heathrow. He says he did it only because he was in despair: his condition had started to deteriorate fast, an arranged marriage had been cancelled because his girlfriend's parents didn't want her to marry a man with such poor prospects, and his half-sister had been diagnosed with cancer. Roque Hall, who had no previous criminal record, was in pieces when he was asked to import the cocaine. The judge later accepted that he had been "groomed and manipulated".

Once he admitted guilt, it was inevitable that he would be given a custodial sentence. The only thing that could have kept him out would have been if the prison in question, Wormwood Scrubs, had said it was incapable of dealing with his complex needs. Roque Hall's mother, Anne, believes that was what the judge was expecting, and hoping, to hear; then her son would serve his sentence at home under curfew or in care.

In court it was made clear that the specialists responsible for his care believed no prison was equipped to look after him. His consultant neurologist told the court about the exercises carers need to do with him through the day and night to palliate muscle pain and constant back pain. He also has to stand in an upright wheelchair six or seven times a day, to maintain what muscle capacity he has. At home, he had at least one carer, often two, 24 hours a day. Anne says the judge looked shocked after Wormwood Scrubs insisted it was perfectly capable of looking after her son. "I jumped up and put myself in front of Daniel when the prison officers came for him, and I said, 'You're not taking him anywhere. I want the governor of Wormwood Scrubs in this court to explain exactly how they are going to look after him because it's a lie and everybody knows it's a lie.' They were all looking at me. In the end I knew I couldn't stop him being taken."

When Roque Hall was being processed at the prison, he fell from an examination couch on to his head. He told medical staff he needed to go to hospital after a fall because he was at risk of haemorrhaging, and they suggested he was faking. Instead, he was sent to a care home, where he was surrounded by patients suffering from dementia. Apart from visits to the lavatory, Roque Hall was chained to a prison guard throughout his six days in the care home.

"It was ridiculous," he says slowly, deliberately. Speech is a struggle. "I'm hardly likely to jump out of the window or make a run for it. At one time I went for a shower, so they removed the handcuffs. When I came back, they put the handcuffs on really tight. I said to the lady that they were too tight and they were pinching my skin; I asked her to loosen them and she said, no, that's how it's supposed to be."

Roque Hall went into a diabetic coma when in the care home and had to be taken to hospital. A few days later, he was judged well enough to return to Wormwood Scrubs, where it appeared that the jail was not prepared for him. Although a physio was brought in to show staff how to use his stand-up wheelchair, they refused to because they said they had not received adequate training.

He lost two stone in seven weeks and suffered dramatic muscle deterioration. While in hospital he had been diagnosed with thyrotoxicosis (caused by an overactive thyroid gland), which can cause severe weight loss. Medical staff at Wormwood Scrubs were told it was vital for his weight to be monitored regularly. "You know how often he was weighed in seven weeks?" Anne asks. "Never. And they actually had a written care plan that said he should be weighed at least once a week."

She looks at her son. "After I saw you there, I just went out and sobbed. I was beside myself." He was rushed into hospital, in chains, on 23 August. "When a nurse phoned me about 3am and said he was in intensive care, I simply said, 'Is he dying?' I think she was shocked that I'd said that. She said, well, he's very, very ill. By the time I got down there Daniel was no longer able to speak. He had a whole team of doctors and nurses around him. All he could do was make sounds like 'bleueh bleueh bleueh'. His eyes were terrified. He was emaciated, he had sores on his face, his hair was long. He'd been utterly neglected. What was he doing with sores on his face?"

It was only when his heart started to give up and he was moved to intensive care that his handcuffs were removed.

Anne, an occupational therapist, finds it traumatic to talk about even now. In the end, Roque Hall did pull through, though he spent the next six months in hospital recovering. His heart consultant said he was in metabolic breakdown, due to the thyrotoxicosis not being monitored.

When he came out of intensive care, he found himself in a ward surrounded by three prison guards. He and the guards were then moved to a room. His mother says the lack of privacy was obscene. "I was very involved in his care. I gave him his speech therapy exercises, I fed him, so the prison officers saw a lot of me. Some of them said, 'We can't give him the care he needs, he needs to be at home with his people.' But some would make notes when we talked or when the doctors came in." When Roque Hall and his mother spoke to each other in Spanish, they claim the guards forbade it.

Eventually it was accepted that Roque Hall could not be rehabilitated with the officers in the room; they were moved outside, with the door left open so they could see everything going on. Before long he was talking and making jokes, Anne says: "And I thought, this is the old Daniel."

In February, the appeal court showed "exceptional mercy" and ruled that Roque Hall should be released from prison early after his lawyers argued that the Prison Service could not meet his medical needs. "His admission to intensive care and six months in hospital would have been completely avoidable," Anne says, "if they had looked after him as healthcare staff should, and as I would have done at home, and if they had taken action much earlier, not just when he was on the verge of dying."

Roque Hall's MP, Glenda Jackson, is horrified that he was handcuffed through much of his ordeal. "It's clearly absurd that a man who could never present a physical danger to anyone should be restrained in this way," she says.

The Guardian's findings suggest that restraint is the starting point for most seriously ill prisoners, regardless of privacy and patient confidentiality issues. In May this year, John Twomey was taken from Whitemoor prison in Cambridgeshire to Peterborough hospital to undergo heart surgery. Twomey, 65, is serving 20 years and six months for masterminding a robbery at Heathrow airport. He has had three major heart attacks; after one, at Belmarsh prison, he was pronounced dead and had to be resuscitated.

Twomey went to hospital in handcuffs, with six guards escorting him. As he was wheeled into the theatre, the heart surgeon said the chain attaching him to an officer would have to be removed. It was pointed out that if his heart needed to be restarted by electric shock, the officer at the other end of the chain would also suffer a shock, possibly severe. The prison staff phoned Whitemoor, asking for permission to remove the chain. It was refused and the operation was cancelled.

On 30 May, Twomey was taken back to hospital. Following a pre-op and electrocardiogram, the surgeon said she was carrying out an angiogram, and ordered the chain to be removed. Officers remained in the theatre throughout the surgery and replaced the cuffs and chain while Twomey was still on the operating table, despite being told he would be unable to move for several hours.

In 2007, Lucy (who doesn't want us to use her last name) was taken from Peterborough prison after suffering a recurrence of a serious gynaecological problem. She was serving a sentence for a non-violent offence and had returned to jail after a day-release on licence. Despite this, she was handcuffed to a male and a female officer on the journey to her hospital appointment. Lucy says she was marched through the hospital reception "jangling like Marley's ghost", and the officers did all the talking. "I wasn't even allowed to confirm my name and date of birth; the male officer repeated my 'address' loudly enough for the whole hospital to hear," she says. She was still attached to both officers when she was called to see the doctor and had to relate her past medical history and current symptoms.

She was told she would undergo an internal examination and handed a gown. The female officer entered the changing area with her and the male officer, with chain still attached, stood outside. She says that the male officer told the doctor he would have to remain with his prisoner in the small, windowless examination room.

"I was going to have an invasive investigation, one that I wasn't overjoyed at the doctor doing, far less having a strange male observing," she says. In the end the doctor persuaded the male officer to handcuff Lucy to the couch and leave the room, leaving the female officer still attached to her. "The over-the-top security was unnecessary, offensive and inhumane," Lucy says.

The Prison Service declined to comment on any of the individual cases in this article. It told the Guardian that it restrains severely ill prisoners only after risk assessments have been carried out. "Public protection is our top priority and prison governors have a duty to mitigate the potential risks prisoners pose to the public, medical staff and other hospital users. All prisoners are risk-assessed before being escorted to hospital, to ensure security measures are proportionate and that they are being treated with dignity and respect."

But prisons and probation ombudsman Nigel Newcomen, who published a critical report on end-of-life care in custody this March, is not so sure. "The issue of inappropriate use of restraints on elderly, infirm and dying prisoners is one that needs to be addressed… While the Prison Service's first duty is to protect the public, too often the balance is not achieved between humanity and security. My office has become increasingly robust in stating where this balance hasn't been achieved."

Kyal Gaffney died, aged 22, three weeks after being sent to prison

for careless driving under the influence. Photograph: collect picture by

Murdo MacLeod for the Guardian

Mary Currie has left her old home and moved several times in

a desperate attempt to escape her past. Her son, Kyal Gaffney, died in

prison in November 2011, three weeks after being convicted of careless

driving under the influence. Mary and her daughter Justine have been

left trying to put their lives back together, but it isn't proving easy.

Kyal Gaffney died, aged 22, three weeks after being sent to prison

for careless driving under the influence. Photograph: collect picture by

Murdo MacLeod for the Guardian

Mary Currie has left her old home and moved several times in

a desperate attempt to escape her past. Her son, Kyal Gaffney, died in

prison in November 2011, three weeks after being convicted of careless

driving under the influence. Mary and her daughter Justine have been

left trying to put their lives back together, but it isn't proving easy.They sit in a living room, surrounded by religious plaques and figurines promising hope and peace, talking about the son and brother who had been an A* pupil at GCSE, with ambitions to be a bilingual lawyer. Then, at 17, his best friend was killed in a car crash. That was when things started to go wrong. Gaffney withdrew from his many friends, became addicted to cannabis, stopped working at school. His A-level results were disappointing and he decided not to go to university. Although he was depressed, he didn't give up entirely. He became a porter, then a healthcare assistant in the hospital Mary worked in as a manager, wrote songs and befriended a boy called Devland Barnes-Bromfield. They soon became inseparable.

It was 2 July 2010, Barnes-Bromfield's 19th birthday, and Gaffney had been telling Mary all day how they were going to celebrate: they were going to get a taxi to a local club and make a night of it. But late in the evening there was a change of plans and he announced he was going to drive to Leamington, 20 miles away, to pick his mate up from another club.

The boys didn't stay long: Barnes-Bromfield and his friends had been involved in a minor fracas. Gaffney, one of life's peacemakers, according to his mother, tried to sort it out, had a bottle of cider, chatted up a girl, then the two boys headed off. On the way home, Gaffney hit a tree: Barnes-Bromfield died instantly. Gaffney was left in a coma, and it was a miracle he survived. He severed the main artery in his leg. "He lost enough blood to have killed him," Mary says. "I remember kissing his head, his face held between two blocks, completely splattered in dry blood. His leg wasn't recognisable as a leg."

After an eight-hour operation, he was kept in a medically induced coma for 10 days; he had 11 operations within two weeks of the accident. Gaffney couldn't remember anything of the crash (let alone the fact that Barnes-Bromfield had been lying dead on top of him when he was rescued, which might well have saved his life). When he was told his friend had died, he refused to believe it. "It was like I hit him on the head with two bricks," Mary says. "Then he just let out the most awful noise. It came from right in here." She points to her heart. "It was like a cat being murdered. He was screaming that it should have been him and he didn't want to live. Then he started pulling out the wires."

Gaffney was initially suicidal, but gradually became positive. He decided he had to make something of his life for his friend's sake. But Barnes-Bromfield's family blamed Gaffney for his death, and wanted to see him prosecuted. Gaffney was charged with careless driving under the influence of alcohol. He was in fact only 0.1ml over the limit after his one bottle of cider. His lawyers told him that if he pleaded guilty, he would be unlikely to face a custodial sentence.

Gaffney was unwilling to accept that he was over the alcohol limit, but he did tell his mother that he had smoked cannabis that evening. Mary knew then that her son would go to jail. Medical experts argued that he should be allowed to serve his sentence on tag at home. "His doctors said they didn't think he should go to prison because he had everything in place in the community for his medical care. His counsellor actually wanted to put him into the psychiatric unit to protect him from going to prison." Gaffney was sentenced to 21 months.

Mary and Justine are convinced the prison, HMP Hewell in Worcestershire, made everything as tough as possible for him. Mary says that the first time she visited him, he had on only one shoe because the prison had not given him his surgical footwear. He was struggling to walk on his crutches and was told he had to climb three flights of stairs to get his pain relief. "And the prison officer is there saying, come on, you can do it faster than that. We found out afterwards, to add insult to injury, that there's a lift in his block." On her first visit, Gaffney complained to his mother of cold, and said he was bunged up. By her second visit, she was worried about his condition. Like Michael Tyrrell, he was prescribed pain relief, to be topped up when necessary – but she says he was denied the top-up and was in agony.

Part of the problem was that Gaffney would not admit just how severely disabled he was. "He told me not to make a fuss," Mary says. "He didn't want to appear to be a wuss. I'd phoned in the week, asked to speak to healthcare, and they wouldn't let me because Kyal was over 18, so they just put me through to the chaplaincy. He looked really poorly on the second visit, and I was concerned because his nose had been bleeding and he'd been bringing up blood for five days. "

Mary and Justine made one final visit to Kyal, on 4 November 2011. "I was absolutely appalled," Mary says. She does slow breathing exercises – three inhalations followed by heavy exhalations – to control her emotion.

"I couldn't believe my eyes," Justine says. "He just looked completely white, and all you could see was this massive bruise on his forehead. We didn't even say, 'Hello, how are you?', just, 'Oh my God, you've been beaten up." But he hadn't been.

"As he started talking, we could see his tongue looking as if it had blood blisters on it," Justine says. "We thought he'd been hit from the back, had hit his head and bitten his tongue. He said, 'No, I had a nosebleed last night and I woke up with all these things on my tongue.' He rolled up his sleeve and he had a massive bruise on his arm. He was really disoriented and his eyes looked glazed. To start with I thought he'd been smoking weed again. I cried all the way home after the visit. I just had this feeling I wasn't going to see him again."

"I phoned the prison when we got home," Mary says. "By this time the chaplaincy had gone and I said, with the greatest respect, it's not a spiritual matter, it's a medical matter. And they said, well, the chaplaincy deals with it and they're not here now, so you'll have to get in touch with them tomorrow."

Kyal Gaffney's mother Mary and sister Justine were with him when he

died – as were his guards. Photograph: Murdo MacLeod for the Guardian

Four days later, Gaffney was diagnosed with leukaemia and rushed into

hospital. Again there were vital delays: his blood was taken in the

morning but not tested till the evening. He was in an observation room

from 9.45pm to 2am, bleeding from his nose. He had suffered a cerebral

haemorrhage. All this time he was handcuffed to a prison guard.

Kyal Gaffney's mother Mary and sister Justine were with him when he

died – as were his guards. Photograph: Murdo MacLeod for the Guardian

Four days later, Gaffney was diagnosed with leukaemia and rushed into

hospital. Again there were vital delays: his blood was taken in the

morning but not tested till the evening. He was in an observation room

from 9.45pm to 2am, bleeding from his nose. He had suffered a cerebral

haemorrhage. All this time he was handcuffed to a prison guard.At 2.15am he became unconscious. "He was in the last hours of his life and they just put him in an observation room with a brown sick bowl, and left him to die," Mary says through a cascade of tears. He was clinically brain dead, still handcuffed to a prison guard. It was only when doctors insisted that the chains be taken off for a CT scan, that they were removed.

"They phoned me up at 3.45am and told me that Kyal had been taken to hospital," Mary says. "I said, oh, we're due to visit him later, will we be able to see him in hospital?" She breathes in deeply. "I asked what was wrong and the man from the prison said, 'You need to go to the hospital, his pupils have blown.'" They really expressed it like that? "Yes. If I wasn't a medical-type person, I wouldn't have known what it meant. But I did know: it means you've bled in your brain." She swallows and breathes. "When we got there, we were taken into a little office and this doctor came and asked us all to sit down."

Two years on, Mary still finds it hard to believe, let alone talk about, what she witnessed. The doctors thought there was one last chance to save her son, by rushing him for emergency surgery at a more specialised hospital. "They needed a doctor and two nurses in the ambulance, but the guards insisted they had to go with him, and there wasn't room."

"I said, 'You should be ashamed of yourselves,'" Justine says. "My brother needs to get in that ambulance, and you are having an argument with medical staff because you want to get in there. He's in a coma and you still think you need to stop him escaping?" In the end, the medical staff agreed to travel with just one nurse and the two guards, but by then it was too late. It was now 6am, four hours since Gaffney had gone into a coma, and doctors decided nothing could be done.

Indignity was heaped upon indignity. Around 30 friends arrived to say goodbye to him before the life-support machine was turned off. "The guards didn't leave the room till after we arrived," Justine says. "They wouldn't allow any of his friends to go in because technically he was still a prisoner. The guards were still there even when the machine was turned off. We said, 'We don't need you here now, you know he's dead. Is that not enough for you?'"

Kyal Gaffney died, aged 22, on November 9 2011. The inquest into his death heard a catalogue of misdiagnoses and unnoticed symptoms, and an occasion when the prison doctor refused to see him. A narrative verdict concluded: "There were a number of missed opportunities for further intervention prior to 7 November 2011. The jury concludes that had further intervention occurred, then it is more likely than not that an intracerebral haemorrhage could have been avoided." In April, a report into HMP Hewell by HM Inspectorate of Prisons concluded that the jail "provided an unsafe and degrading environment".

Ask most prisoners what their main fear is and they will tell you it is getting ill in jail – a fear that seems to have been exacerbated by the privatisation of healthcare services in prison and the impending withdrawal of legal aid for prisoners to challenge neglect by prison staff. While the cases examined here are extreme, the charity Inquest believes they are indicative of common failings in prison healthcare. Deborah Coles, co-director of Inquest, says: "This demonstrates a shocking abuse of power, and a total lack of humanity towards dying, seriously ill and disabled prisoners. These are not isolated cases but illustrative of a systemic pattern where principles of humanity and decency have been usurped in the interests of security, and where the use of restraints is the default rather than the exception. Such policy interpretation must be urgently reviewed to prevent further ill-treatment and to ensure restraint is used only in the most exceptional circumstances."

Back in Salisbury, Michael Tyrrell's daughters are convinced that if he had been diagnosed earlier, he would still be alive. They point to a photograph of a cheerful, larger-than-life man happily listening to the Salvation Army in prison, taken just a few months before he died. But for now this is not the way they remember him. The image they are left with is of an emaciated man lying in a hospital bed, chained to a prison guard, waiting to die.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire